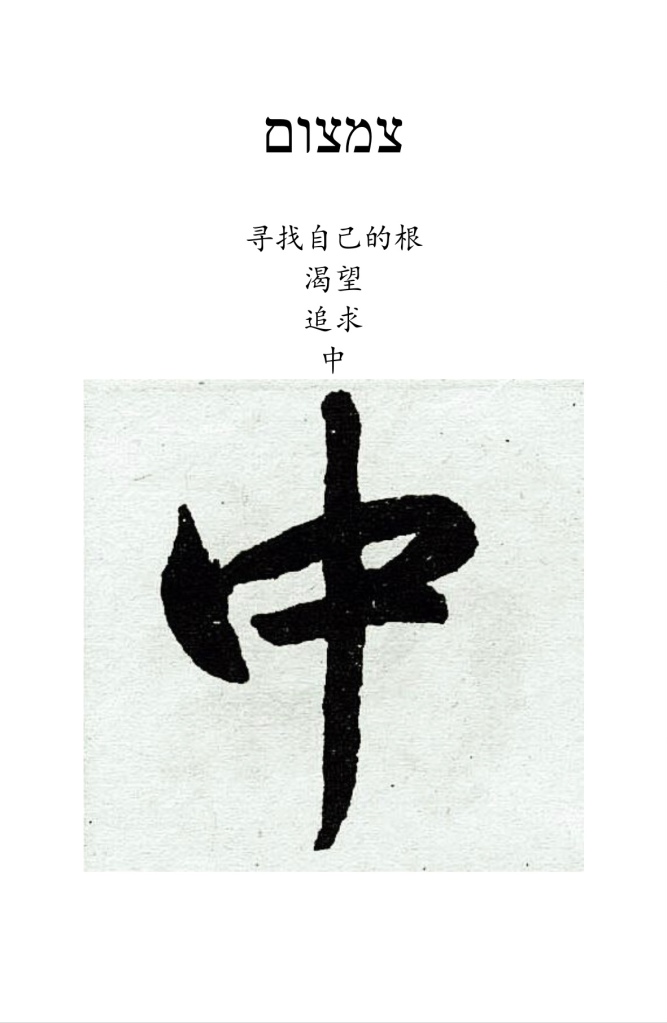

“China would be my way out. Chinese would be my way in.”

I’ll first start with a parable from the Baal Shem Tov. It is the book ends to my story.

A parable from Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov:

A King had an only son, the apple of his eye. The King wanted his son to master different fields of knowledge and to experience various cultures, so he sent him to a far-off country, supplied with a generous quantity of silver and gold. Far away from home, the son squandered all the money until he was left completely destitute. In his distress he resolved to return to his father’s house and after much difficulty, he managed to arrive at the gate of the courtyard to his father’s palace.

In the passage of time, he had actually forgotten the language of his native country, and he was unable to identify himself to the guards. In utter despair he began to cry out in a loud voice, and the King, who recognized the voice of his son, went out to him and brought him into the house, kissing him and hugging him.

The meaning of the parable: The King is G‑d. The prince is the Jewish people, who are called “Children of G‑d” (Deuteronomy 14:1). The King sends a soul down to this world in order to fulfill the Torah and mitzvot. However, the soul becomes very distant and forgets everything to which it was accustomed to above, and in the long exile it forgets even its own “language.” So it utters a simple cry to its Father in Heaven. This is the blowing of the shofar, a cry from deep within, expressing regret for the past and determination for the future. This cry elicits G‑d’s mercies, and He demonstrates His abiding affection for His child and forgives him.

This story is archetypal for Jews throughout our history. It is part of the cry that has occurred in our souls to which G-d responds in every generation. We go off, become immersed in the societies where we are, and our souls forget the language they were born with.

It is that moment of decision that is a moment of crisis too which with persistence turns into sweet sweet bitterness.

It is the point in our lives when we have everything but something is still missing. A soul which forgets its language can only cry out. A visceral response by both body and mind. Our soul’s cry is the sudden and unearthly realization that we must return to G-d. There we are. Just like Abraham, immersed in a culture and civilization that is so advanced and sophisticated, caught by the startling revelation that we will, like he, follow that call. We will “leave” our “homeland” seeking something more true.

It is the same agonizing cry which began with and punctuated all my travels.

Not only did I leave in a spiritual sense I did so in the geographical sense going to the furthest place possible away.

This is my story of transforming that cry into something workable. By route of Southwest China, Taiwan, Hongkong, Bhutan, Thailand; by way of a language, Chinese, which appears impenetrable, I would learn the language of my Jewish soul.